Called as Olai Chuvadi or Eattu Chuvadi, the palm leaf manuscripts played a key role in the development of the language

Escaping the city’s heavy traffic congestion in an hour’s drive you can reach a rural pocket of Coimbatore, whose identity is a landscape dotted with tall Palmyra trees in the background of a vast blue sky. While most children of modern Coimbatore hardly know even the traditional eatable Nungu (Tender palmyra fruit) and the beverage Pathaneer (Sweet toddy) being the produce of the Palmyra tree, it is no wonder that the parents of the present day inform little to their kids on the contributions of Tamil Nadu’s national tree to the documentation of Tamil language and literature.

Called as Olai Chuvadi or Eattu Chuvadi, the palm leaf manuscripts played a key role in the development of the language, since all the classical pieces of Tamil literature had been written only on them before they came out in book form.

Besides literary writings, the palm leaves were also used to carry the dicta of kings, orders of government and personal journals. Though such writings were later inscribed on copper plates and stone slabs, they were first drafted only on palm leaves.

With palm leaves being different in their kinds as Naattupanai, Koontharpanai and so on, the ones used for writing were appropriately called Olaivettupanai. For making a ‘notebook’ for writing a script, the leaves from Olaivettupanai were cut and shaped at their edges. They were later soaked and boiled in water before dried for hours in shade. Then they were rubbed with pebbles to facilitate writing on them. And people wrote on them with a pen called Ezhuthaani using a kind of black ink mixed with yellow colour.

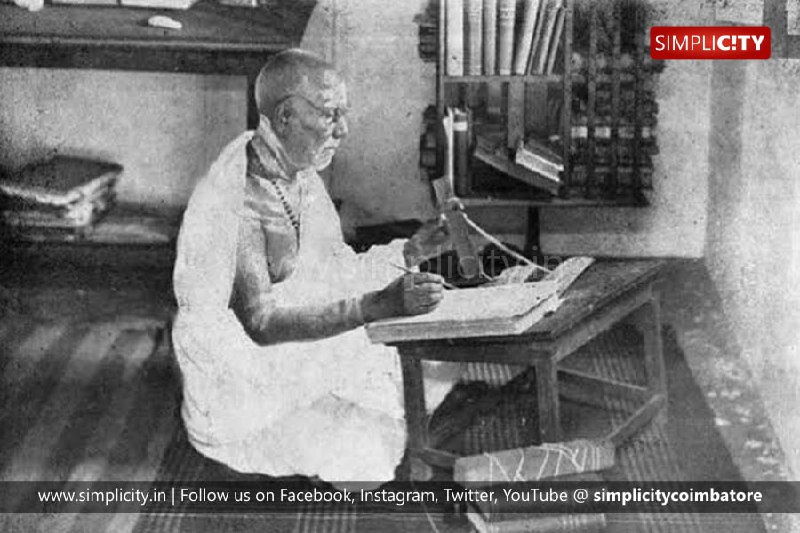

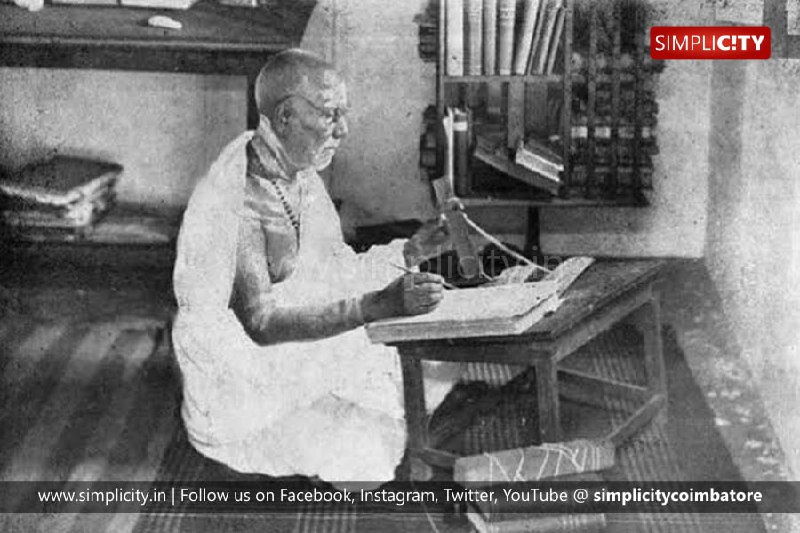

Though numerous pieces of ancient Tamil literature including Silapathikaram and Seevaka Cinthamani were discovered and brought into print form by noted researcher and Tamil scholar U V Saminatha Iyer long ago, certain palm leaf manuscripts of Kongu history and literature like Kodumanal Ilakkiyangal, Kongunaattu Samuthaaya Aavanangal, Kongu Vellalar Seppettu Pattayangal and Appachimar Kaviyam have come as printed books only in the last few decades.

As said above, while inscribing the text of a palm leaf manuscript on a copper plate or on a stone slab, the inscriber also gives his byline below the text, as read from Perundurai Cheppedu, which reads as ‘Ippattayam Ezhuthinavan Venkulooru Sithakolla Aasaari’. Interestingly, certain stone inscriptions discovered in the Kongu region contain even signatures of the people!

Today, an unlettered man gives his thumb impression as the alternative for his signature on a sheet of paper. But, how could the illiterate sign on a stone inscription in ancient days?

Even the present day society uses the Tamil derogatory expression ‘Tharkuri’ to name an illiterate person. But, ‘Tharkuri’ literally means a mark inscribed on an epigraph, which was nothing but the unlettered man’s predecessor for today’s thumb impression!

Called as Olai Chuvadi or Eattu Chuvadi, the palm leaf manuscripts played a key role in the development of the language, since all the classical pieces of Tamil literature had been written only on them before they came out in book form.

Besides literary writings, the palm leaves were also used to carry the dicta of kings, orders of government and personal journals. Though such writings were later inscribed on copper plates and stone slabs, they were first drafted only on palm leaves.

With palm leaves being different in their kinds as Naattupanai, Koontharpanai and so on, the ones used for writing were appropriately called Olaivettupanai. For making a ‘notebook’ for writing a script, the leaves from Olaivettupanai were cut and shaped at their edges. They were later soaked and boiled in water before dried for hours in shade. Then they were rubbed with pebbles to facilitate writing on them. And people wrote on them with a pen called Ezhuthaani using a kind of black ink mixed with yellow colour.

Though numerous pieces of ancient Tamil literature including Silapathikaram and Seevaka Cinthamani were discovered and brought into print form by noted researcher and Tamil scholar U V Saminatha Iyer long ago, certain palm leaf manuscripts of Kongu history and literature like Kodumanal Ilakkiyangal, Kongunaattu Samuthaaya Aavanangal, Kongu Vellalar Seppettu Pattayangal and Appachimar Kaviyam have come as printed books only in the last few decades.

As said above, while inscribing the text of a palm leaf manuscript on a copper plate or on a stone slab, the inscriber also gives his byline below the text, as read from Perundurai Cheppedu, which reads as ‘Ippattayam Ezhuthinavan Venkulooru Sithakolla Aasaari’. Interestingly, certain stone inscriptions discovered in the Kongu region contain even signatures of the people!

Today, an unlettered man gives his thumb impression as the alternative for his signature on a sheet of paper. But, how could the illiterate sign on a stone inscription in ancient days?

Even the present day society uses the Tamil derogatory expression ‘Tharkuri’ to name an illiterate person. But, ‘Tharkuri’ literally means a mark inscribed on an epigraph, which was nothing but the unlettered man’s predecessor for today’s thumb impression!